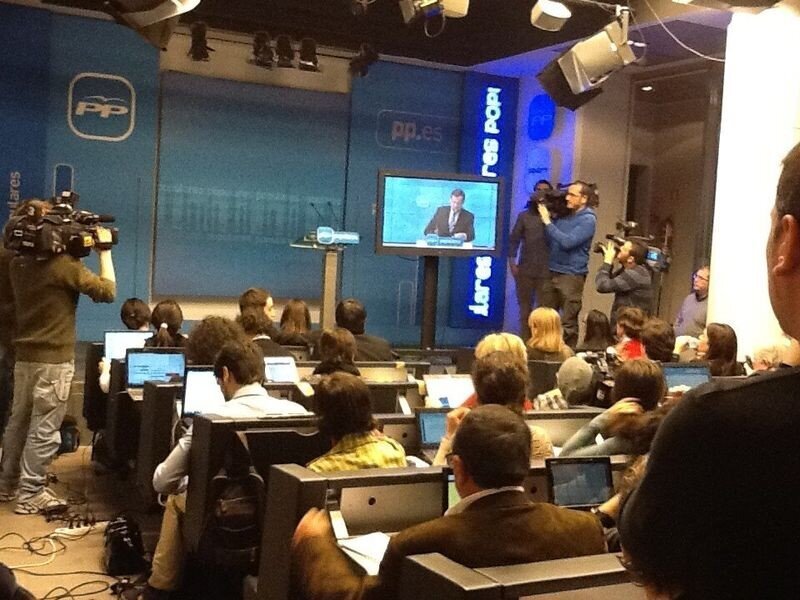

Madrid, 27 February 2013 – The picture says it all: a government embattled by corruption scandals is so reluctant to answer questions that it puts journalists in a separate room during a press conference. This happened on 2 February 2013 for a press conference given by Spanish premier Mariano Rajoy.

The objective was to avoid being put on the spot by uncomfortable questions about the governing Popular Party’s finances.

It’s sometimes hard to follow what is going on in Spain: The leading political party and even the royal household are embroiled in corruption scandals. In response, everyone is talking about “transparency” but the sub-standard access to information law is making slow progress through the parliament.

Access Info Europe’s director Helen Darbishire, who has been in Spain for over six years promoting the right of access to information, answers questions about what is going on and how the current corruption scandals affecting the campaign for open government?

Q: Where is the access to information law now?

Helen Darbishire: The draft Law on Transparency, access to public information and good governance is currently being considered by the Constitutional Commission of the Parliament (Congress). The version currently under consideration is that submitted to the parliament by the Spanish cabinet (the Consejo de Ministros) on 27 July 2012; see statement by Cabinet office (in Spanish). To the best of our knowledge, and in spite of various promises in response to criticisms of the draft, it has not been changed since.

The proposed access to information law was prepared by the right of centre Popular Party after it came to power in elections held in November 2011 with a promise to present a transparency law in its first 100 days.

The first draft, made public in March 2012, was roundly criticised by national and international experts. Over 3,700 people participated in a two-week public consultation on the draft in early April 2012. Although the government never published a report on the consultation, a leaked internal report showed that the majority of respondents had called for the law to be significantly strengthened.

In Access Info Europe’s analysis, the proposed law will not permit Spain to ratify the Council of Europe Convention on Access to Official Documents.

Q: What are the next steps? When will the law be adopted?

Helen Darbishire: The Constitutional Commission of the Parliament has held two hearings to discuss the draft, one on 23/01/2013 and one on 07/02/2013, with eight external invitees giving comments on the draft law. Not all those invited are specialists in access to information; indeed, one university professor even said in his intervention that he did not know why he had been invited.

On the other hand, neither Access Info Europe nor the 65-member Coalición Pro Acceso which has been pressing for 6 years to have a law adopted have been invited to comment; a public statement of concern was issued the Coalition last week, see here. [2]

Assuming the current government does not fall, the law should be adopted before the summer recess of 2013. It is unlikely that it will be subject to any major reforms which will mean that the world’s newest access to information law will also be one of the worst.

Q: Might the government fall? Are the corruption scandals that serious?

Helen Darbishire: The current government is immersed in a potentially massive corruption scandal which is making its position look very untenable. Its popularity according to the opinion polls is low – the ruling party had a 29% approval rating before the current corruption scandal broke.

Nevertheless, the ruling party has an absolute majority in the parliament with 186 out of 350 parliamentary seats following the November 2011 elections; elections are normally held every four years in Spain.

Q: What is this corruption scandal about?

Helen Darbishire: Spain’s ruling Popular Party (PP) is caught in a web of corruption which has shocked even the Spanish public used to hearing about the dodgy relations between political parties, business men, construction companies and failing banks.

At the heart of the current scandal is the man who was the PP’s treasurer during 31 years, Luis Bárcenas, who has somehow managed to accumulate millions in Swiss bank accounts. According to what Bárcenas himself has told investigating judges, at one point he had €38 million in the Swiss accounts; it is not yet clear where this money came from.

News breaking this week indicated that leading PP members have been lying to the public about the fact that Bárcenas was employed in the party headquarters, on a salary of over €200,000 per year, even though he had been formally charged in another major corruption scandal in 2010, the Gürtel case. [3]

On 31 January 2013 the newspaper El País published documents which show that senior members of government including, allegedly, the Prime Minister, were receiving off-the-books payments using funds donated to the party by businesses. The government has yet to comment fully on these allegations and is systematically avoiding giving comprehensive answers to questions from the media.

For more on the case, see El País in English.

Q: What does this have to do with the financial crisis?

Helen Darbishire: Perhaps the most outrageous thing for the Spanish public is the fact that the ruling politicians seem to have been receiving salaries without paying taxes on them, while a large percentage of the population – 26% overall and over 55% of young people – is unemployed, and everyone has been hit by a series of tax rises and cuts in essential public services.

Q: With all this concern about corruption, why did Access Info Europe have to pay €3000 in court fees for asking about ant-corruption measures?

Helen Darbishire: In 2007 our board member Juanjo Cordero presented an information request asking the Ministry of Justice what the Spanish government was doing to implement the UN Convention against Corruption and the OECD anti-bribery convention. We went to court after an initial administrative silence and then a response to our administrative appeal saying we didn’t have a right to ask.

Quite simply, we lost the case before the Supreme Court and had to pay €3000 for the time of the Spanish government lawyer in defending the case.

The Spanish Supreme Court ruled that civil society does not have the right to demand “explanations” from the government – it stated that only the parliament has that right.

Access Info Europe had asked the court to rule on the fundamental nature of the right to information and had argued that this should be considered as part of the constitutional protection of freedom of expression; the court did not rule on this point.

Access Info Europe has appealed the substance of the Supreme Court Ruling to Spain’s Constitutional Court but as no further appeal was possible on the costs, we have now paid these to the government and they go into the general budget.

In the context of the rampant corruption in the political class in Spain, the reluctance to provide information on what is being done to fight corruption is perhaps not surprising, but it is still shocking.

Q: What impact will the corruption scandals have on the transparency law?

Helen Darbishire: In response to the corruption scandals, the word “transparency” is often heard from politicians, although often in the broader sense of “integrity” or “accountability” rather than strictly ensuring greater access to information understood as the right to request or receive information.

In January 2013, Access Info Europe and the Foundation Civio launched an online petition calling for the political parties to come under the scope of the access to information law; it was signed by over 176,000 people. The response from the government has been to say that “the criteria of the Transparency Law will also apply to political parties” [4] but this is not the same as proposing an amendment to the law.

The Prime Minister also said that these transparency principles would also apply “all bodies financed by public funds” and “business organisations and trades unions” – but again, this is not the same as formally expanding the scope of the access to information law.

Q: What is wrong with the draft law?

Helen Darbishire: There are a series of problems with the law, which covers proactive and reactive disclosure of information but also, uniquely among the world’s 93 access to information laws, also has a chapter on good governance which establishes sanctions for violations of other laws related to administrative conduct, ethics and conflicts of interest.

Some of the more significant problems identified by Access Info Europe and national and international experts include:

» It’s not a right! The current draft law fails to recognise the right of access to information as a fundamental right. The biggest consequence of this will be the complications when it comes to applying the new norm across Spain’s complicated federal system.

» Privacy will prevail: Another crucial consequence is that the law does not have the same status as the right to privacy, which is strongly regulated in Spain and vigorously applied to deny access to information containing the names of individuals.

» Limited scope: The scope of the proposed law is limited to bodies which are subject to administrative law, and in particular does not apply to the legislative and judicial branches.

» Limited information: The notorious Article 15 of the law excludes vast amounts of information from the right to ask, including “auxiliary or supporting Information such as the content of notes, drafts, opinions, summaries, and communications and internal reports shared within or between public bodies.”

» Defers to other laws: A further provision, the First Additional Disposition, makes the transparency law secondary to any information which is subject to a “specific legal regime for access to the information.”

» Weak oversight: The proposed oversight body (the “Transparency Agency”) is dependent on the government and its powers are not specified in the draft law.

These shortcomings in the law are of particular concern because our monitoring in Spain shows a level of administrative silence which is around 50% and with only about 15% of requests getting answers which obtain the information sought. This is a serious lack of transparency in practice which can only be changed by a strong access to information law.

Q: And what is good about the draft?

Helen Darbishire: The draft law has a series of proactive transparency obligations, many of which reflect existing requirements or practices. It also establishes a basic mechanism for the public to ask for information, upon provision of identity of the requestor, an address, and the details of the requested information, and establishes a one-month response period.

Requestors do not have to give reasons, but this is undermined by a provision which says that they “can include reasons” and that if they do, these will be taken into consideration when deciding upon the request.

Q: Isn’t Spain a member of the Open Government Partnership?

Helen Darbishire: Yes! In theory at least. Spain signed up to the OGP on 31 August 2011 in a letter which stated that the country “shares [the OGP’s] objectives and planned activities.” [5] On 11 April 2012 an action plan was sent by the Spanish government to the OGP Secretariat and it can be found here. This document had been released as a draft in Spanish language version to a limited number of civil society representatives on 3 April 2012. There was no time for a proper debate, but Access Info Europe reacted rapidly with its comments of 9 April 2012 which can be found here. The English language version submitted to the OGP on 11 April has no significant modifications (it is marked as definitive). There is no publicly available version in Spanish on any Spanish government website.

Since then there has been no public consultation on the action plan. On 4 October at the OPG meeting in Dubrovnik, a Spanish government representative was asked in a public meeting about the consultation on the action plan and said simply “no news”. On 10 December, at an OGP regional meeting in Italy, the same government representative, Esperanza Zambrano, General Secretary for Legislative Proposals in Spanish Cabinet Office, stated that a new action plan was in preparation. At time of writing (25 February 2013), no further news has been communicated to civil society.

The Spanish government has no dedicated web space with information about its involvement in the OGP. There have been no updates on progress made in delivering on the commitments in the action plan.

Q: What’s likely to happen next?

Helen Darbishire: It’s very difficult to tell but there are a number of key things which people can look out for, starting with any changes in the government in response to the corruption scandals as these changes could impact – either positively or negatively – on the transparency law.

Next observers of Spain should look out for news on any proposed changes to the access to information law. Experts and campaigners are calling for the draft text to be strengthened. The question is whether the current political crisis will be enough to persuade the Spanish authorities to bring the law into line with international standards.

The political – and economic and social – situation in Spain is very fragile right now. In Access Info Europe we are sincerely hoping that the government responds to this by doing the right things when it comes to improving transparency and strengthening democracy and open government.